Social Life's Olimpia Mosteanu blogs about the challenges and possibilities for place-based research during COVID-19, reflecting on what the Social Life team have learnt since March 2020, and how we used these insights to carry out research into quality of life at home.

COVID-19 has unfolded simultaneously as a public health, social and economic crisis, raising constant doubts about what responsible place-based research looks like during such extraordinary times. In reflecting on how the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted place-based social research, the first thing to note is the ever-changing nature of these challenges.

Under ‘normal’ circumstances, we would make use of place-based methodologies to understand the lived experience of people in relation to their communities and neighbourhoods. This includes face-to-face interviews, walking ethnographies, door-to-door surveys and public space observations.

This post starts by reflecting on the general challenges we have faced in the last few months and some of our responses, which have allowed Social Life to continue carrying out place-based research. It then goes on to describe some of the specific ways in which we have adapted our research to respond to the COVID crisis by focusing on one project we conducted between May and July 2020 exploring quality of life at home.

Challenges and doubts

The pandemic has posed three major challenges to place-based social research.

Our team looked for responses to the challenges brought about by the crisis. The relationship between places and people is at the centre of our work. If place-based research is to shed light on local needs and support policy responses we felt this work remains as important as ever during the COVID-19 crisis.

This has led us to:

Possibilities and hope

In March 2020, the Social Life team was involved in research about how people perceive the built environment’s impact on their quality of life across the UK for the Quality of Life Foundation. The research design relied on face-to-face street interviews and involved people living in a range of settings across the UK. Two weeks into the fieldwork, the COVID-19 crisis brought the research to a halt. Shifting the research design allowed us to continue the study and carry out fieldwork between May and early June 2020. The research questions were amended to capture the role played by the home environment and the local area in supporting or undermining quality of life during the lockdown.

Using a flexible research design allowed us to be prepared for a period of quick changes in COVID-19 regulations: in May, the UK was under tight restrictions and non-essential retail and facilities were closed but as the month progressed there were some slight relaxation of lockdown restrictions in the different UK nations.

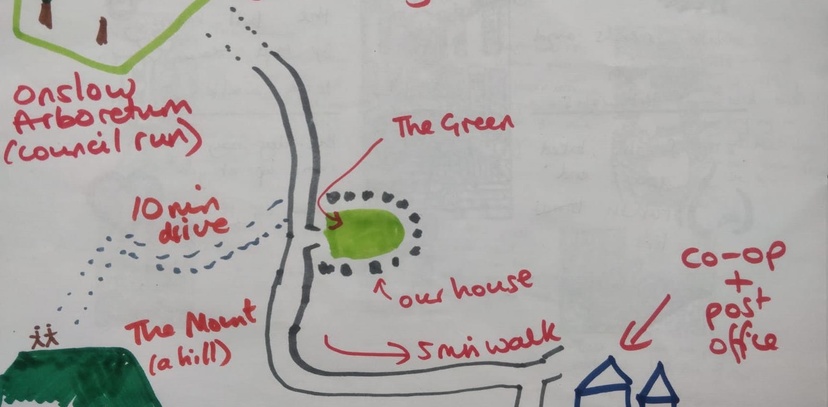

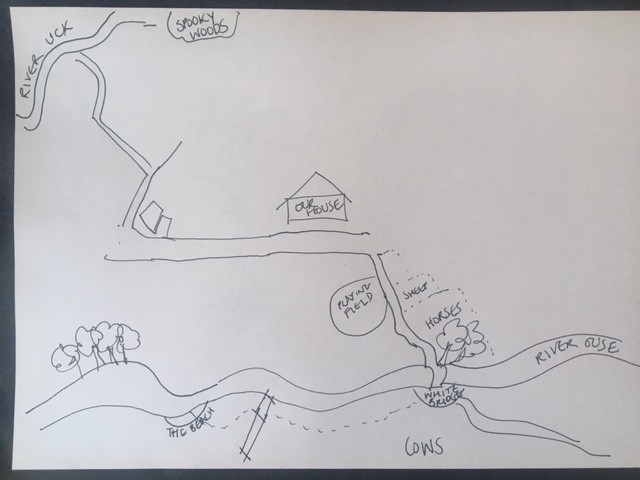

We adopted a mixed-methods research design, combining in-depth telephone interviews, participant photography, and cognitive mapping. We asked participants to send us two photos of spaces in the home where people spend a lot of time; two photos of spaces in the local area that they still use during the lockdown (for example shops, chemists, launderettes, markets, bus stops, parks; one photo of a hand-drawn map of places, amenities or facilities in the local area that were relevant to daily life during the lockdown.

We carried out 53 in-depth telephone interviews and received about 200 photographs and 35 maps. The visual components of the research helped us secure ‘a sense of place’ and build empathy with research participants.

Many of the maps and photographs we received captured places, landmarks and routes between different locations. Cognitive maps usually range from complex drawings at scale that include all major characteristics of an area to simple sketches of routes between locations. The maps we were sent showed not only local places but also how people used and felt about their local areas. They allowed participants to capture their knowledge of local areas, while grounding our telephone interviews in specific places, routes and local experiences.

Being flexible, mixing things up

The combination of methods provided us with a rich understanding of the material experience of moving through local areas, emotions, and nested scales of lived experience (home, building, street, neighbourhood). Cognitive maps showed how limited people’s local worlds became during lockdown as their daily or weekly routes included only visits to local shops and green spaces. The streets themselves became key assets as they were used for daily walking, jogging or cycling.

We learned that daily routines such as cooking or reorganizing one’s space stabilised the notion of home, helping people create spaces of domesticity and intimacy. The in-depth phone interviews, photographs and cognitive maps together illustrate that local facilities not only connected residents to one-another but also allowed them to feel part of their neighbourhood.

“It’s beautiful here, really appreciate where we live. We've got to see it properly, really enjoyed getting out and exploring it every day, finding new spots and places. I've been here 25 years and I’m still finding new places to explore. It’s a really good place, you have the same faces that you get to know, but then you also get the tourists in the summer which makes it interesting.”

Together, photographs of homes and the in-depth telephone interviews gave us a rich insight into the social and emotional dimensions of changes in the home during lockdown. The visual and oral accounts illustrated the pressure of working from home, while others focused on the need to adjust to being together with others in the same space, day after day.

“We've added a table in the parents' bedroom where my son has been doing his schoolwork…My wife setup her home office in the basement/guest room… My daughter has been using an area in the living room, next to the kitchen, so there was someone on every level of the house.”

Learning as we go

We learnt important lessons about carrying out responsible and responsive place-based social research during the pandemic.

Useful resources

COVID Realities website, https://covidrealities.org/research/webinars .

Crowdsourced document initiated by Deborah Lupton. “Doing Fieldwork in a Pandemic.” March 2020. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1clGjGABB2h2qbduTgfqribHmog9B6P0NvMgVuiHZCl8/preview

Social Life “Social Research during COVID-19” webinar recording, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DxyMLbY6DOQ&t=276s .