The Aylesbury Estate has a unique presence both in its local area, and within wider discussions and debate around housing and regeneration policy. In late 2020 and the spring of 2021 we spoke to people living on the estate, local agencies and community organisations. We wanted to find out their experience of the changes in the area, and of living through the pandemic - building on research we carried out on the estate in 2014-15.

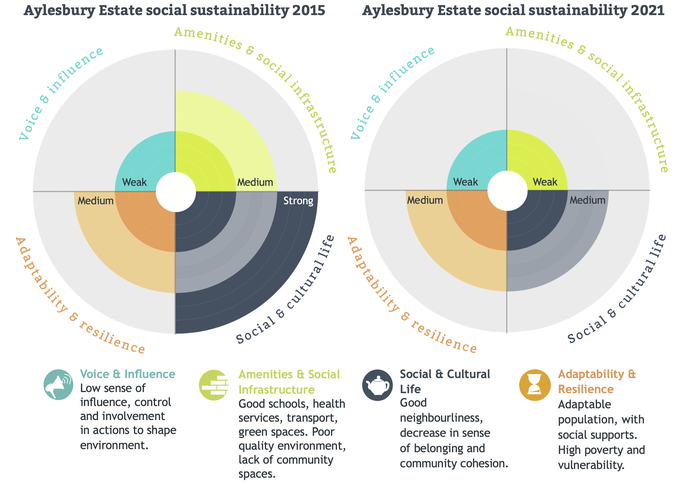

We heard a story of how the particular process of the Aylesbury regeneration and the crisis of the pandemic have undermined many of the protective factors that have supported local communities in the past - in particular the social infrastructure and the social assets within the community. But we were also told, in spite of this, that some of the estate’s strengths remain: its services and facilities, and the sense of neighbourliness and belonging that seemed so strong when we first spent time in the area.

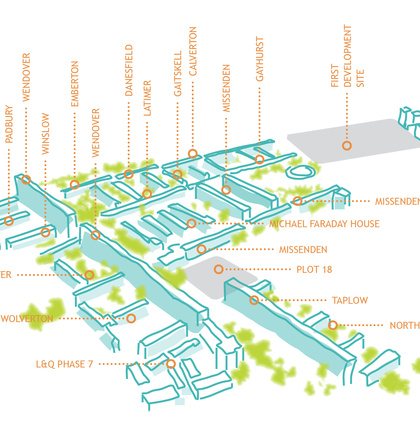

This is the second stage of our research for Notting Hill Genesis to track the impact of the redevelopment of the estate, which is being incrementally demolished and rebuilt. The Aylesbury Estate is iconic within Walworth, its slab blocks demarcate a particular geographical area and community which became synonymous with inner-city decay, poverty and crime from the 1980s onwards. In 1997 it was the venue for Tony Blair’s first major speech as Prime Minister, announcing his new administration’s approach to deprived neighbourhoods and to welfare reform, and describing Aylesbury residents as among “the poorest people in our country [who] have been forgotten by government.”

Over the five years different factors have taken their toll on everyday life. Disrepair has increased alongside dissatisfaction with housing. Social networks have been undermined as longer standing residents of blocks that are to be demolished move out; and new residents arrive. These include two main groups, people on temporary tenancies moving into homes that secure tenants have left, and new residents of newly built homes, some of these are from more affluent backgrounds. All this change has taken place against a backdrop of insecurity linked to the profound change the area is going through, and the uncertain progress of the regeneration.

Images: new homes built by L&Q and one of the older red brick blocks on the estate

In 2020-21 we heard we heard how social relationships, social networks and the work of local agencies had helped people get by in difficult circumstances, but how these were put under strain in the pandemic. COVID revealed the numbers of people who were living very precarious lives.

We were told that residents’ sense of voice and influence is very low, that people often feel powerless and that they have little control over what happens in the area. These feelings seem to have been exacerbated by the visible decline of the condition of the estate and a feeling that the council have been unable or unwilling to manage its upkeep. Satisfaction with housing is very low. The physical condition of the estate, and the lack of community spaces and facilities, is not supportive of residents’ individual and collective wellbeing. However, good public transport, schools, health services, Burgess Park and other parks as well as strong and active third sector organisations continue to support everyday life.

The increasing number of residents in temporary accommodation (many with vulnerabilities and difficult life stories), often feel they have very little say or feeling of investment in the estate. People told us they felt safe overall, however the blocks that are emptying are becoming serious magnets for anti-social behaviour and crime.

There are very mixed feelings about the regeneration. As residents see blocks coming down, there is a sense of inevitability that they will have to leave their homes. Residents can see new housing being built, but is not clear to them when they will be able to move in. Most council tenants want to stay council tenants despite many having animosity towards the council for the poor condition of the estate – earlier this year it was announced that 581 homes on the first redeveloped site will be council housing rather than housing association homes, as was initially planned.

Our first benchmarking research in 2014-15 found a place where a number of protective factors were supporting residents and helping them cope with difficulties, although many were living on very low incomes and navigating complex lives. We found social solidarity and tolerance between different groups, and neighbourly and often friendly relationships between people living in close proximity.

Residents we spoke to told us that they felt comfortable living on the Aylesbury, they felt they belonged. Many newer residents described a welcoming place, accepting of people from a wide range of backgrounds. People also often described significant problems with the physical condition of the housing. These local assets had not evaporated by 2021, but they had been diluted by the amount of movement in and out of the estate and the impact this had on social networks and social supports.

We used our social sustainability framework as the starting point for our assessment in both rounds of research. This captures four dimensions that we see as being key to a thriving place: Voice & influence; Social & cultural life; Adaptability & resilience and Amenities and social infrastructure. Looking at the change in scores over time reveals how the estate has changed, highlighting the fall in the quality of Social & cultural life and Amenities & social infrastructure.

The Aylesbury regeneration has been deeply contested and controversial. Our work shows the difficult impact of the last five years and of the pandemic on the local assets and protective factors that supported residents in the past, and how the impact of the regeneration over the last five years has increased the number of people living in precarious situations while undermining social supports. There are wider implications for the way that the social assets of social housing estates are valued and protected during times of change.

The COVID-19 crisis exposed the extreme poverty and the difficulties many Aylesbury residents face. As new blocks are built and new facilities like the community centre and library are built, we hope that they will be able to support the community as new pressures from sharply rising costs of living bite, against the backdrop of continuing regeneration and change.