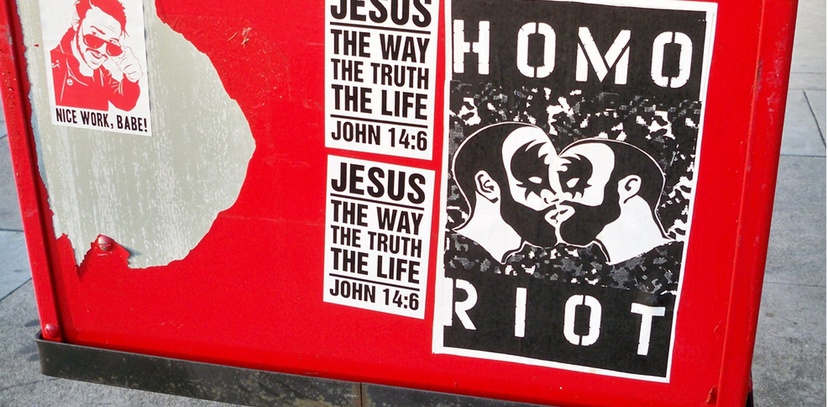

Over the last few years, Social Life intern Claire Malaika Tunnacliffe has been documenting LGBTQ+ graffiti and street art in public spaces. She has co-opted the word placemaking, typically used as a community-building tactic to connect people and places, and given it a queer reading.

I was visiting New York in late 2016 when I stumbled on the rainbow stenciled words “BE PROUD”. In that moment, two things happened: (1) as a woman in a relationship with another woman, I felt seen and acknowledged. And (2) I was reminded of how much of myself I edited out in public spaces to feel accepted and safe.

It has been my experience that places remain spaces of straight privilege because the very act of holding my partners hand in public remains a transgressive act. It’s an act which continues to raise eyebrows and stares, if not harassment or assault.

From left: Athens | July 2017 | Cacao Rocks, Dublin | October 2017 | Writer Unknown

Back in London, I'm left wondering how to create a sense of belonging as a queer person. While, gay bars, prides or gayborhoods are incredibly important assets, where else are there opportunities to see the everyday lives, histories and stories of the LGBTQ+ community?

These spaces, cornerstones for many LGBTQ+ people's lives & coming out experiences, are enormous assets but are increasingly at risk of closure with 58% of LGBTQ+ spaces shutting their doors since 2006. They are also in equal parts neglected and co-opted, with many redevelopment projects and urban planning policies that seem inherently homophobic in in not speaking directly to the LGBTQ+ community’s needs, or supporting LGBTQ+ spaces and histories in future plans for London.

A recent UCL Urban Lab report stated, “LGBTQ+ nightlife spaces have accommodated a range of important welfare, wellbeing and community functions. At a time of rising inequality and intense competition for space, closures of venues and other spaces present a challenge for already vulnerable minorities, for the neighbourhoods in which they form part of the social, cultural and economic fabric, and for social integration in the capital more widely”.

While multiple venues have had to shut their doors, including Madame Jojo’s, the Black Cap, Barcode Soho, Kazbar, the Queen’s Head, Candy Bar, the Oak Bar and Green Carnation, other venues have won important battles. For example, in November 2014, the Royal Vauxhall Tavern (RVT) was sold to property developers in a multimillion pound commercial deal. Soon after, the campaign group RVT Future was formed to defend the venue's continued use as a site of LGBTQ community and culture and submitted an application to Heritage England, the RVT was made a Grade II listed building on 8 September 2015, the UK's first building to be listed in recognition of its importance to LGBTQ community history.

From left: Peckham | Oct. 2017 | Writer Unknown, Philadelphia | July 2017 | Unknown

Queer placemaking resists definition. Placemaking, place-making, place making (depending on your choice spelling) at first glance seems to contradict, the words dancing with or against each other. Making, in the process of being made, is destined to never be complete. Place is considered both as the “hard” structural material of spaces, as well as its “soft” emotional entanglement with memory, belonging, and identity. Queer also resists definition, acting both as noun and verb, with its meaning changing over time. Once spat out as insult, it has been reappropriated by more recent generations of activists, and is now affiliated with sexuality and gender identity, politics and activism, academia (queer theory) and spatially (queer spaces).

Birmingham | Sep. 2017 | The Masked Muskequeers

I wonder if these slippages of meaning offer a way of opening up new understandings on multiple perspectives of placemaking, belonging and identity for LGBTQ+ individuals and communities. In this way, LGBTQ+ graffiti and street art found across city surfaces, offer a window into the lives of others.

Graffiti and street art can que(e)ry place and reveal the dominant power dynamics within public spaces. It is in the in-between, stencilled on the walk to work, stickered to the traffic lights while waiting to cross the road, painted as a mural, or sprayed across hoardings, that a little reminder is wedged: You may not be seen or safe to be you at home, at work, or in the street, but there are others just like you that exist and move in the same spaces. Queer placemaking as LGBTQ+ graffiti and street art, is a reminder that you are not alone.

Unknown | May 2017 | Tatyana Fazlalizadeh

Claire Tunnacliffe is an MPhil/PhD researcher at the Bartlett School of Architecture exploring queer activism and placemaking. Follow her on twitter @C_Mali.

Images are sourced via History of Queer Street Art and Queering The Streets.

Cover image: California | 2011 | HOMO RIOT