Will the pandemic change how we use and design our homes and neighbourhoods in the future?” Woolwich, southeast London, March 2020. Photo Olimpia Mosteanu.

Social Life's work in local neighbourhoods centres round our conversations and interactions with residents. Over the last few weeks we have come to an abupt halt in all our planned face-to-face research in local areas. We are not alone in this, the experience is shared by a wide community of people doing in-depth work in places, in applied research agencies like ourselves and in universities.

Online approaches fill some gaps, but we know that responses are skewed towards the more affluent and the views reported in on- and offline research can be very different. So we urgently need to find new ways of speaking to people and reporting their views and expriences that respond to the strange times we find ourselves in.

We want to connect with others who are trying to find ways to carry out in-depth qualitative and ethnographic research in these times of pandemic, to share resources and ideas and lessons about what works.

Social Life's Olimpia Mosteanu has been reflecting on these issues and asking how we understand the impact of COVID-19 on our homes and neighbourhoods.

For the last couple of weeks, the impact of COVID-19 on the field of social research has received increasing attention. I would like to add to those conversations by reflecting on the specific challenges facing place-based research brought about by social distancing and lockdown measures around the world.

In this blog, I consider the impact of COVID-19 on research designs commonly used for the study of the social life of places. Place-based social research is focused on the lived experience of people in relation to their communities and neighbourhoods, as well as on the resources embedded in their networks and the challenges facing them. Place-based research sees neighbourhoods and communities as palimpsests—social landscapes on which people have been writing and rewriting their stories together—which is why it relies on methods that explore the layers of lived experience grounded in place. Places emerge from a variety of social relationships and people’s engagement with their surroundings. At the same time, places come to life when people interact with one another.

Stamford Hill northeast London, March 2020. Photo Jonah Rudlin.

Many place-based studies combine forms of participant observation with face-to-face interviewing, allowing researchers to gain insight into both ‘what people do’ and ‘what they say’. These mixed-method research designs bring together traditional methods such as door-to-door surveys and more innovative methods such as street interviews and walking ethnographies or ‘go-along interviews’ with local residents. These are useful ways to gain rich, experiential insight into how local people engage with their physical and social environments in their everyday life. However, social distnacing and lockdown measures introduced across the world mean that these data collection methods and the accompanying approaches to selecting sites and participants are now being reassessed.

Is it possible to carry out place-based social research right now?

Some voices have argued that perhaps we should put all social research on hold in an attempt to ensure the safety of both researchers and participants, and to direct all existing resources towards public health efforts. Others have argued that, if social research is to have a role in informing key public policy during a pandemic, engaging in social research is more necessary than ever. That said, it is abundantly clear that social research needs to respond to the need for social distancing, which is why a number of crowdsourced lists of research resources have been shared across academic networks in the past two weeks (links to these resources are the end of this blog).

In addition to the data collection methods, place-based research designs will also have to carefully address issues related to site and participant selection, especially when research involves low-income residents, single mothers, unemployed people, undocumented immigrants, older adults on fixed income, among other groups. Research studies could provide a lens into wellbeing, networks of support, and struggles, all valuable information at the moment. However, decisions regarding adequate research designs need to take into account that these groups are disproportionally impacted by the pandemic because their support networks, time availability and safety nets are drastically limited and under pressure.

At a time when there is so much uncertainty regarding sick pay, making rent, mortgage and debt payments, job stability for those on fixed-term contracts, and future prospects for the self-employed, place-based researchers should expect that research participation among groups could be uneven. This will affect the representativeness of studies in ways difficult to predict. Furthermore, as Sharon Ravitch noted, it is our responsibility as social researchers to establish research ethical guidelines that put an emphasis on compassion and awareness of each other’s burdens during the pandemic.

In light of all this, I wonder, how can we responsibly and responsively engage in place-based social research under the current circumstances? How can we design new research studies and re-design studies that were supposed to make use of face-to-face methods in ways that address the current risks and limitations? How can place-based studies be designed with flexibility and openness in mind given the evolving impact COVID-19 will have on neighbourhoods and the changing government responses to it? Below you can find one possible combination of methods that aims to offer a practical, responsive and, hopefully, sensible approach to the study of the social life of places during a pandemic. For other takes on mixed-method approaches to place-based research, I recommend going through the myriad of resources in the crowdsourced lists at the end of this blog.

One among many

In some cases, a combination of phone/online interviews, photo elicitation and cognitive mapping might offer a feasible and responsive way of gathering data for place-based research. This mixed-method research design is suitable for exploring people’s experiences of specific neighbourhoods. It can make use of semi-structured interview guides focused on themes such as: place attachment at multiple spatial scales (home, building, neighbourhood); local cohesion; best and worst aspects of living in the local area; everyday routines; challenges and opportunities grounded in place.

A snowballing technique can be used to expand the sample of residents by inviting initial participants, identified through key stakeholders, to recommend other residents that might be interested to take part in the research.

Photo elicitation is a qualitative research method that, in its most common form, uses photographs taken by research participants to stimulate additional engagement and insight from them. The method adds a strong visual dimension to the research design. Photographs of places inside the home and of local areas can elicit participants’ experiences of the physical environment in which they live, such as homes, snapshots of local businesses where they usually meet up with others under normal circumstances (shops, cafes, pubs, charities, fruits and vegetable markets, etc.), open green spaces, and community spaces (youth clubs, gardening club, childcare facilities).

Example of a photograph for a photo elicitation exercise. Thamesmead, southeast London. March 2020. Photo Olimpia Mosteanu.

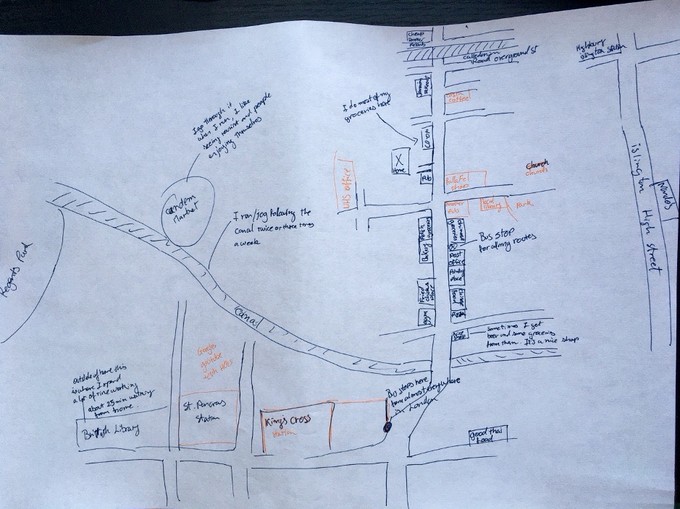

A cognitive mapping exercise can be used to generate additional insight during the phone or online interviews. This exercise consists in drawing a map of places, services or resources the participants use in their local area. Participants are asked to send the map together with the other photographs of places before the interview takes place. These visual materials can be used to ground conversations about the social landscape and thus secure a nuanced understanding of participants’ lived experiences.

On the one hand, the lived experience of people in place is captured as self-reported perceptions and descriptions of behaviours. On the other hand, we are able to record rich details about experiences that often people themselves do not think about – such as how people move in their surroundings, how people instinctively avoid certain spaces because they do not feel entitled to occupy them, the role of daily routines, etc. This could help us better understand the networks, facilities, and other aspects of the physical and social infrastructure people rely on and value in their local areas. These sometimes go unnoticed to people themselves in their daily lives because they are taken for granted but they become visible as soon as the everyday order is disrupted.

These research methods provide complementary insights. Just like with more traditional research designs used in place-based social research, the most appropriate combination of methods depends on research timelines, financial resources and staff constraints.

These are just some of the practical and ethical challenges, and options, we need to keep in mind when replacing traditional interactive methods with other means of carrying out place-based research during a pandemic. At a time riddled with anxiety and uncertainty, place-based research designs need to remain sufficiently flexible in order to accommodate the shifting needs and burdens placed on individuals, neighbourhoods, and the research community itself.

Perhaps this could be a time when we experiment together with forms of co-producing knowledge in a pursuit of a research process based on dialogue and exchange of experiences.

I hope my reflections can serve as a platform for dialogue and you feel encouraged to share your experiences of carrying out research about places during these challenging times.

Useful resources:

Crowdsourced document initiated by Deborah Lupton. “Doing Fieldwork in a Pandemic.” March 2020. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1clGjGABB2h2qbduTgfqribHmog9B6P0NvMgVuiHZCl8/preview

Ravitch, Sharon. “The Best Laid Plans…Qualitative Research Design during COVID-19.” 23 March 2020. https://www.methodspace.com/the-best-laid-plans-qualitative-research-design-during-covid-19/

LSE Digital Ethnography Collective Reading List SHARED DOC. March 2020. https://zoeglatt.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/LSE-Digital-Ethnography-Collective-Reading-List-March-2020.pdf

Taster, Michael. “Editorial: Social Science in a Time of Social Distancing.” 23 March

"This could be a time when we experiment together with forms of co-producing knowledge in a pursuit of a research process based on dialogue and exchange of experiences."