Recovering from the Olympics, post gold medal euphoria, looking forward to the Paralympics, there is a new preoccupation in London about how we hang on to the good times after September. For the communities living around the Olympic site, the legacy has a starker implication: will promised jobs and new wealth materialise for this part of London's East End, where poverty rather than opportunity has traditionally been the norm?

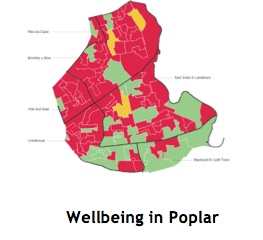

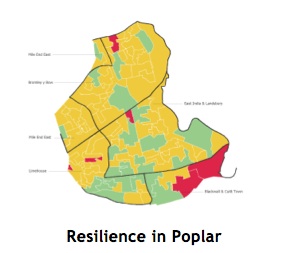

Earlier this year Social Life was asked to quantify community wellbeing and resilience in the part of East London directly south of the Olympics site, in Poplar, for the Institute for Sustainability.

Using the WARM (wellbeing and resilience measurement) tool developed by the Young Foundation we mapped wellbeing (life satisfaction) with resilience (ability to bounce back in the face of adversity) by small local areas. Overall the area had low wellbeing but higher resilience, tough but not very happy, typical of many areas of both high public housing and relative disadvantage.

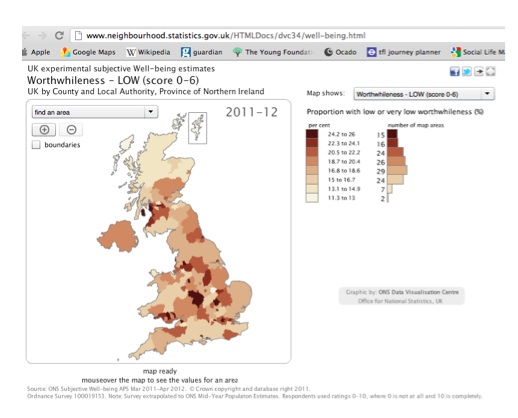

New data released this summer from UK's National Statistics Office, ONS, plus new analysis from the Young Foundation is revealing the complexity of wellbeing, and misery, in local neighbourhoods and communities, and what makes some places happy, whilst others slump.

ONS's map reveals where satisfaction, happiness, anxiety and worthwhileness are located. Inner London residents report feeling particularly worthlesss and anxious. But in terms of happiness and wellbeing, we score similarly to our less worried and more fulfilled neighbours in outer London.

Other places where people report strong feelings of futility are in the West Midlands, North West, parts of Scotland and Wales. The unifying factor is that all these places are amongst the less affluent - but also in this list are places like Bristol that are less often included on deprivation hotlists.

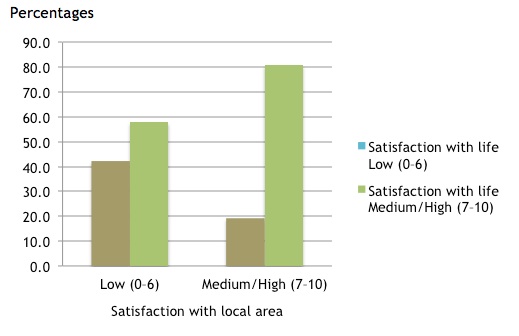

ONS also paint a strong relationship between people's sense of satisfaction with the area they live in, and their overall life satisfaction. People who are happy with their lives are also happier with where they live. But the data doesn't show what is cause and what is consequence, whether we like the areas we live in because we are (generally) at ease with the world, or whether enjoying the place we live makes us happier overall.

Satisfaction with local area compared with life satisfaction, Great Britain, 2011-122

Source: Opinions Survey, Office for National Statistics

New analysis from the Young Foundation, published in the Wellbeing and Resilience Paradox, explores new psychosocial data from the Understanding Society Survey to probe the relationship between wellbeing and resilience, asking under what circumstances these two things, commonly believed to be linked, move in different directions? The report from the Young Foundation reveals that that 35 per cent of people are either 'satisfied but vulnerable' or 'dissatisfied but tough' (with the overall figure split broadly between the two groups).

Output Area Classifications (OACs) were used to extrapolate these results to local areas. Unsurprisingly, affluent communities have the highest levels of both wellbeing and resilience. Communities characterised by public housing feature amongst those communities with low wellbeing and low resilience.

Communities that are happier, but vulnerable (with high wellbeing and low resilience) tend to be older, with higher proportions of single households, as well as communities described as having 'typical traits' - whose demography is similar to the national.

Conversely, communities that are tough but dissatisfied (low wellbeing but high resilience) include younger blue-collar families, living in terraced housing communities and renting public housing. Higher resilience possibly comes from strong social networks and sense of belonging.

A community with both higher resilience and wellbeing will be in a better position to deal with the coming years as recession bites and public services and the economy continue to restructure.

Understanding how wellbeing and resilience play out at local level is new territory and what is most interesting is the so what? We can map Poplar by life satisfaction, but how does this knowledge change its future? How can this understanding help communities and those who work on their behalf?

Londoners found that the Olympics made us feel better about ourselves and the city we live in. If this effect is going to last, we need to get better at working out the very local dynamics of wellbeing and resilience, and understanding how this relates to tangible actions. This would be a fantastic Olympic legacy.

The Wellbeing and Resilience Paradox by Nina Mguni, Nicola Bacon and John F Brown was published in July 2012.

The ONS's first annual experimental subjective wellbeing results were published in the same month.

This blogpost was written by Nicola Bacon.