Namji Kim, Social Life's secondee from Seoul Metropolitan Government, shares her reflections on Barking and Dagenham's Every One Every Day programme.

Among public sector officials in Seoul or London, Bentham's utilitarian principle of maximum happiness still seems to hold sway – the aim being to allocate and spend funds where the most amount of people can participate and benefit. Yet raising participation is a question many of us who work in local government grapple with. The team at Participatory City are looking for and testing answers to this question. They are leading the Every One Every Day project aimed at increasing citizen participation in the outer London borough of Barking and Dagenham.

The Barking and Dagenham area is a relatively deprived part of Outer London with above average crime levels. The project will take place over at least five years, with a budget of over £6 million (10 billion won) for this period. With a longer time horizon than many projects, the Participatory City team and the council aim to change the local DNA and increase participation in the long term. I was interested in understanding more about the project because it relates closely to my research in London looking into citizens’ role in designing an inclusive city.

Participatory City holds open workshops three to four times a year, which allow them to share learning from project and receive input. I attended a workshop in October. My main question after reading up on Every One Every Day was whether this experimental project can be sustainable in the long term? At present, with a budget of just over £1 million per year (2 billion won), the project employs full time workers to carry out various activities with citizens, without this support would participants be able to stand on their own feet? In Seoul I was involved in a project with a wood-working organization set up to support our aim of creating a shared city. We recognized the value of this project, however we knew that without public support it would not be able to carry on – this is the dilemma faced by many public and social sector initiatives, with pressures on public funding meaning many are often not sustained in the long term.

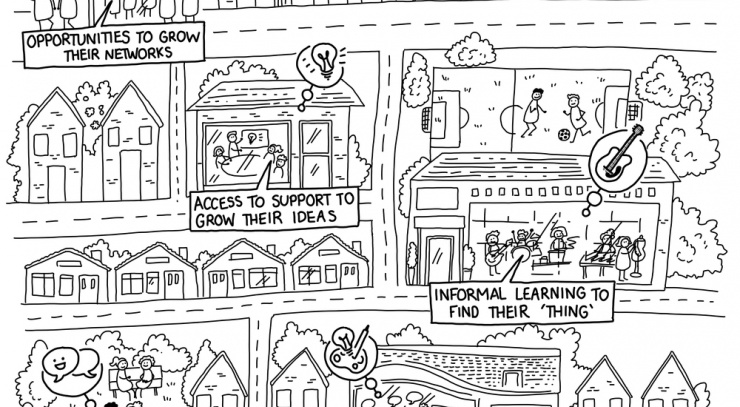

More than 20 people gathered at the workshop. Every One Every Day is a project that many people, including government officials, researchers and the social sector are watching with interest. The all-day workshop consisted of explanations and field visits - currently, the project runs one warehouse and five Every One Every Day shops around the borough. In the morning, staff explained how the project was progressing in the area and what the council wanted to achieve. In the afternoon, we visited the local office where the project was based and met with some of the residents who are most actively involved in the project.

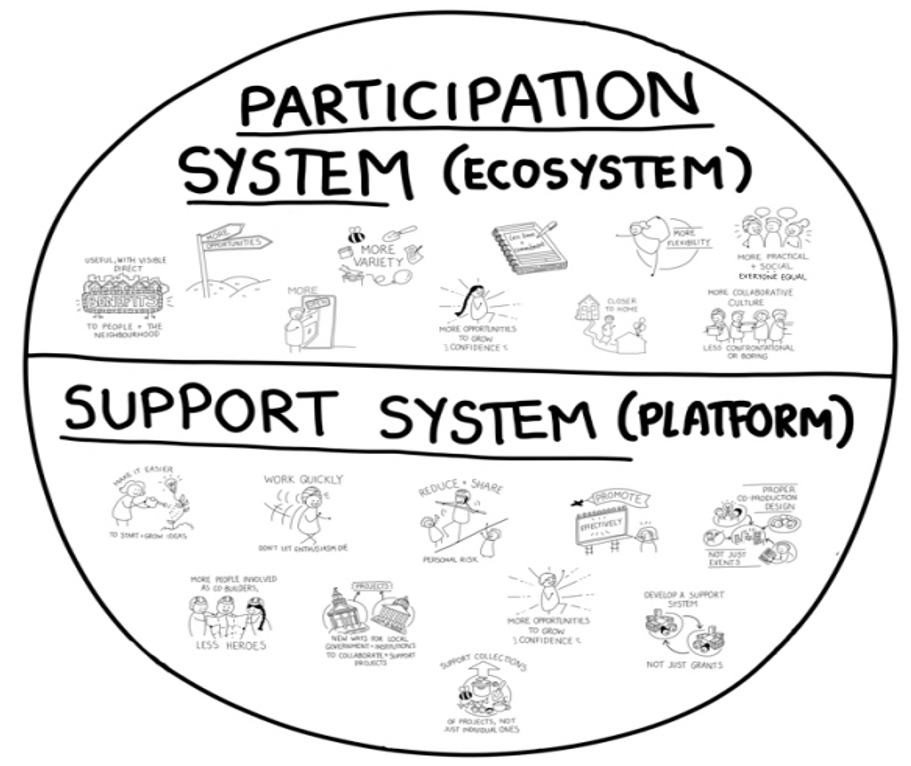

According to a 2015 University of Essex survey of 50,000 people, only 3% of the UK population are participating in local projects, although 60% intend to contribute to the development of their area. So Participatory City studied why people didn't participate and why projects often disappeared, and as a result, they argued that in order to sustain

participation, programmes should be configured into two systems: a participation system and a support system.

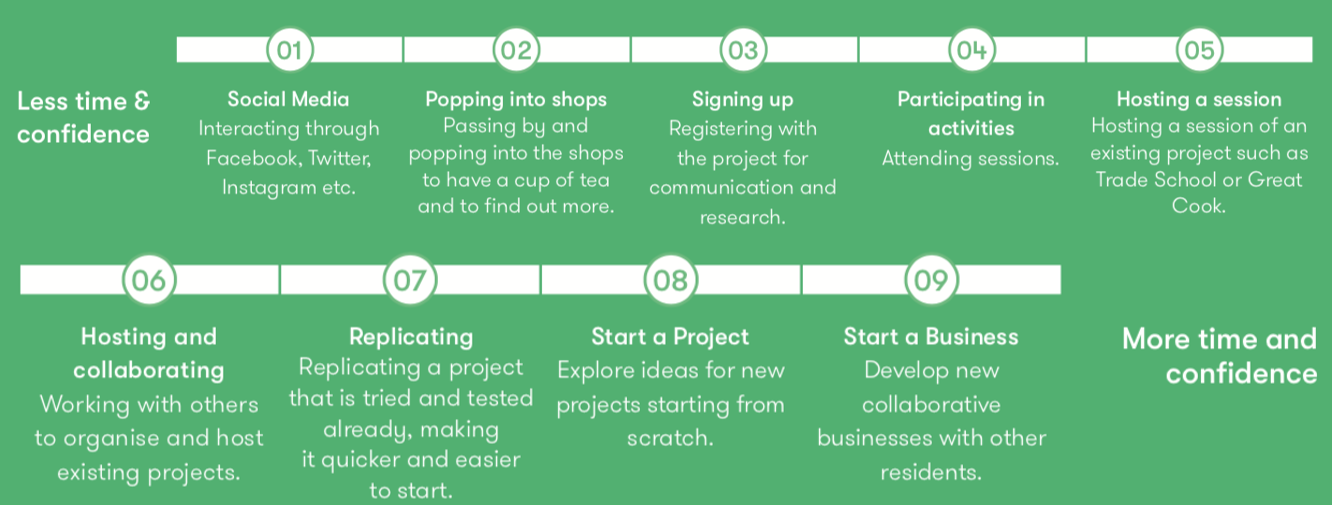

Because each person has a range of time available and different interests, they argue this needs to be recognized through opportunities for both low-level participation and high-level participation, set out below.

This was a very interesting point for me. Since 2019 Seoul Metropolitan Government has also been pushing for a local lab "Neighbour Power Plant" to help more residents participate in daily activities and resolve local issues. In order to create an ecosystem for residents’ participation, the government has established pop-up shops, hobby activities and club meetings to arrange network parties between gatherings. It is interesting that the two cities, while geographically far apart, are aware of the same problems and making various efforts to promote civic engagement.

For me, questions remain about how we can support a larger variety of activities for people to participate in. The activities created as part of Every One Every Day, such as a community lunch, gardening and arts & crafts, are similar to those we put on in Seoul as part of our Making a Village project aimed at increasing participation – I think there is an opportunity and need to create a more varied programme which could engage a wider range of people. The question of how to ensure financial sustainability also remains outstanding, yet if Participatory City’s five-year study clearly proves the change in the community caused by the participation of residents, the case for ongoing public spending may be proven.

If Participatory City’s five-year study clearly proves the change in the community caused by the participation of residents, the case for ongoing public spending may be proven.