The view of the informal settlement from Jingmei Park. Still Image from the Q.K short film

Being Alive on In/tangible Margins: Reflecting on the Queer Kidneys short film pre-production as social re-search in Taiwan in a time of pandemic

Angiet Chen, a Taiwan-based artist and director, blogs about Queer Kidneys & Digital Myths (Q.K), a social re-search in the form of a short film production informed by social media engagement on Instagram. This was created during the COVID-19 pandemic.

After returning to Taiwan in 2020, Angiet’s mental health decreased due to the socio-psychological isolation and got worse by sequential consequences brought by the global pandemic. Later on, I was diagnosed with minor kidney failure caused by the chronological stress from being queer and living under precarious conditions. I initiated this project, responding to the intangible manifestations of violence while creating meanings for the kidney physiotherapy prescribed to heal the organs.

This blog is a reflection on the use of Instagram online engagement spanning across the inception to the pre-production stage of the Q.K project.

The Q.K project started simply as a documentation of my life in social isolation in Taiwan. As someone who heavily relies on Instagram to get instant updates from my loved ones in the UK and Europe, I began to post short videos and photos that captured the kidney physiotherapy – a walking routine with a strange therapeutic heated device attached on my lower back - on Instagram stories (which you can find here).

“To make a new world you start with an old one, certainly.”

After a few posts, I started to wonder how my followers and friends would see the country that I never found any sense of belonging with. I then curated the contents from the visual materials I captured during the therapy walks to post on Instagram. Surprisingly, I got inbox messages inquiring about the posts. Those interactions encouraged me to pay attention to the present moment while being both physically and mentally unwell.

Then, one space sparked the interests of me and my audience (those who have been following me for a long time on Instagram). The space consists of a straight through-route that is adjacent to a former informal settlement, a part of it is now a cluster of recyclable rubbish. Both the route and the cluster are located on the margin of Jingmei Park. The cluster is managed by a socio-economically deprived old couple.

In the webinar, I explained my standpoint – one that is situated in my lived experiences as queer in Taiwan and in against the fetishized representation of queer – that demands re-search in the social realms for subverting the usual systems. I also talked about the pandemic being a great time to conduct social re-search. Before the physiotherapy started, I walked through this space many times. However, I was ignoring the numerous narratives and lives it contains. The social values imposed on my subconscious decided that it was only an urban threshold with rubbish around.

The through-route with the former informal settlements on the left, Jingmei Park on the right and the recycling cluster further down the path. Still Image from the Q.K short film.

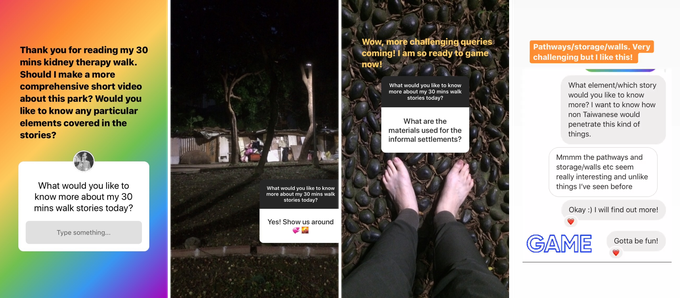

Instgram online engagement for cross-territorial fieldworks.

The entry point to the true discovery and knowledge of this marginal urban space (including its constituents) is formed by the online engagements with the Instagram Stories. Those expressions of care and genuine interests to a foreign land are multi-purposeful: they not only maintained an online network for having social intimacy, but also enquired about the conditions of a dislocated space through me, or say, the caring agent.

To further the online engagement, I went on to learn who the old couple are, their needs, what time they work in the cluster and what stories do they know about Jingmei park. The deployment of Instagram online engagement sheds lights on the creative potential of a social research project (or a re-search if agreeable) a bit further. I’ve entered the stage of script development to explore this matter following an experimental framework.

“Conquest is not finding, and it is not making.”

Until now, no one can say when and how would the world find a way out of this crisis. Ironically, the Q.K project was born out of a personal crisis coinciding with the pandemic. The engagement on my Instagram, sometimes seemingly irrelevant or out-of-the-blue, bears great possibilities.

Nevertheless, I find the trickiest thing to be the discrepancy between at least two realities. Covid-19 barely affects Taiwan – the government controls the spread of the virus by locking down the borders to an extreme extent – it never had to have a single internal lockdown. Meanwhile, fear of the virus and unknown changes strengthens the fixation to old normal (old systems) across Taiwanese society. This will create obstacles to engage with/recruit Taiwanese audiences in the future.

The culture of using Instagram in Taiwan is characterised by neoliberal marketing and hunt-for-novelty media paradigms; posts of middle-class lifestyles, polished visual representation of arts, knowledge and products are the most popular content. That said, the Q.K project, as a critical social film production relying on social media engagement, would need to cultivate a niche audience both inside and outside of Taiwan.

A dedicated Instagram account is a community of differences.

On the other hand, all these factors also mean that the Instagram account remains a small but dedicated one. The benefit is the decent protection and respect a small account could guarantee since I don’t intend to over-expose the subjects in this social re-search/short film production. Secondly (but not necessarily), a small, dedicated account mainly consists of friends and long-term followers and therefore provides a foundation for building trust in a vast digital world like Instagram. This type of trust, although nebulous, is as important as the trust needed for a social research project in a face-to-face scenario. Instagram provides an affordable and intimate environment for the making of long-term, trans-territorial engagement.

Archives of the Instagram stories with responses from friends/followers based in the UK and other countries.

“To find a world, maybe you have to have lost one.”

The objective of the Q.K project is to create digital myths in the form of a short film (or a series of shorts). I have talked about how online engagement on Instagram led to the discovery of a physical location across borders. Here, I would like to talk about how it serves the creation of the outcome.

Since the late 2000s, social media platforms became (in)famous for mass-communication/mobilisation. Individual voices got heard. Propagandas, shared-beliefs (or misbeliefs) are circulated at tremendous scale. The space for subjective interpretation of things is infinite on social media platforms. This also means the disappearance of the world that grounds “truth”. Indeed, this exact impact of social media mainly causes mayhems.

However, the Q.K project aims to leverage the goodness of social media. Without any available official account of a history of the urban margin, Instagram engagement informs the process of accessing its “body”. The subjective responses and questions from my followers are the clues to many unknown presences. This exact speculative nature of Instagram online engagement enables this social re-search to create a mixed genre, which I consider to be digital myths.

The husband (right) of the old couple talking about the history of Jingmei park. One resident inquired about the conversation (left). Still Image from the Q.K short film.

We are witnessing how the pandemic is taking many precious, precarious lives; the aged, disabled, unprivileged, and lower-class. With no guarantee when the stories and lives existing in the through-route and Jingmei park will be forgotten/taken away, I only hope that Q.K project could preserve them. After all, myths are always told by human society, and, they serve truth.

“Conquest is not finding, and it is not making. To make a new world you start with an old one, certainly. To find a world, maybe you have to have lost one.” Ursula Le Guin 1981

Angiet Chen is a former architect and holds an MRes degree in Fine Arts and Humanities at the Royal College of Art in London. They practice storytelling and placemaking in the crossover between physical and virtual realms. Their works take shapes in immersive experiences, indie-games, videos & films as well as curatorial programmes. They collaborate with UK organisations and individuals via digital means.

They can be found on Instagram as @theodor_ussay, an online persona as the protagonist of the Q.K short film.