Social value is often understood as the tangible impacts that flow from a particular change, or intervention, that have social benefit - improving jobs for local people, stopping people smoking, reducing reoffending, greening a building. A wide range of potential issues and metrics. But if we want to see how changes in our built environment have social benefit (or not) then we need to caputre the impact on wellbeing and our perceptions of our lives and the places we live, as well as making material improvements.

This blog highlights some of the work we have been doing to measure these less tangible facets of social value - our wellbeing, sense of safety, relationships with people around us and our sense of belonging - and where we have put this into practice in north east London, thinking about the Woodberry Down Estate and the Hackney Carnival.

How we feel about our lives and the places we live, are vital to our quality of life. A change that makes us more comfortable in our homes and neighbourhoods is creating social value. However the links betwen these intangibles and specific changes and interventions can be oblique, tracking connections and causality is difficult. It's obvious that estate regeneration will change housing conditions, less obvious that it will impact on levels of belonging (positively or negatively); obvious that street improvements increase the number of people walking but there is less interest in how this can change local social relationships.

Two years ago we helped the GLA put together the monitoring framework for the Good Growth Fund fund - creating a set of indicators that projects could choose from to monitor and evaluate their work. The framework includes tangible outputs - square meterage of workspace created, reduction in crime, numbers of jobs created on the living wage - and outcomes measures tracking perceptions of everyday life - sense of influence, perceptions of neighbourhood change, wellbeing. We're seeing how this works in practice working with Haringey Council to evaluate the Enterprising Tottenahm High Road programme with NEF this autumn.

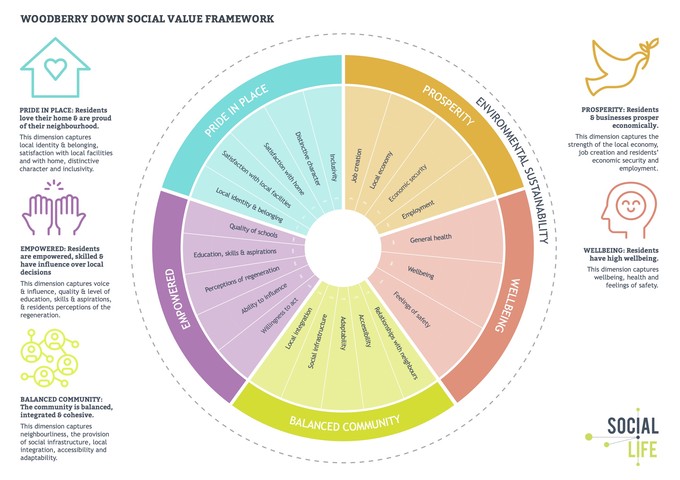

Directly south of Tottenham, in 2018-29 we worked with all the partners in the Woodberry Down regeneration to jointly create a monitoring framework for the estate (this recent film includes the voices of different people involved in the changes on the estate). Hackney Council, Woodberry Down Community Organisation, the residents' organisation, Manor House Development Trust, Notting Hill Genesis and Berkeley Homes took part in workshops to discuss shared aims, and what should be measured. In the future the different agencies will feed their data into the framework to caputre the social value of regeneration across all the different initaitives.

Woodberry Down workshop February 2020

Benchmarking research in 2019 showed that people living on Woodberry Down report relatively strong sense of neighbourliness, wellbeing, belonging and relationships between people from different background, however there is a stark different between people living in different tenures., and the research showed how people on temporary council tenancies (mainly people housed under the homelessness legislation) have lower quality of life than social housing tenants, home owners and private renters. Future research will see whether the regeneration generates social value to close the gaps between these very different experiences.

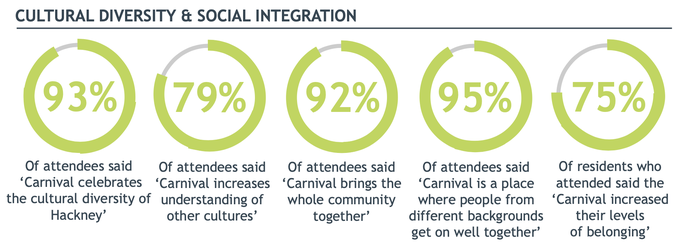

Moving east to the centre of Hackney we worked with Hackney Council and Hatch Regeneris in 2019 to understand the social and economic value of the Hackney Carnival. We used many of the same metrics as we did on Woodberry Down to understand the social value of this very local and very well loved event, which is sadly cancelled for this year.

From the survey of visitors to the 2019 Hackney Carnival

Capturing the social side of impact is inevitably messy because it straightaway butts up against the complexities of our lives and how we live them collectively and individually. But the fact that it's tricky shouldn't stop us trying, and it's only when we undertstand how major changes to built environment effect quality of life in its broadest sense that we will be able to manage change in a way that works for everyone.