Mixed and balanced communities have become buzzwords within UK urban planning during the last two decades, especially within the last ten years. A report from the NHBC Foundation, published in September 2015, concluded that mixed tenure is now an integrated part of the UK life[1], and that mono-tenure belongs to the past. Current housing policy and funding constraints have made mixed tenure a necessity in any scheme that is building affordable homes (apart from the very few cases where cross subsidy comes from another source).

We have become curious about what is known about the impact of mixed housing, particularly on residents living in areas with high deprivation. Our interest has been driven by our experience of living and working in London, in neighbourhoods which have recently seen an explosion of construction and new house building. So we set out to review the evidence. By mixed housing we include a number of different policy initiatives: mixed tenure, balanced communities, mixed communities, housing tenure diversification, and tenure integration.

All the evidence we use is in the footnotes, there is also a bibliography of the reports we reviewed at the end of this post.

One of our most striking findings is that most evidence on mixed housing dates back ten years or more. The smaller amount of more recent research tends to highlight negative effects for vulnerable residents[2]. So even though mixed housing has become central to housing policy, evidence of its benefits is ambiguous. Where official writing and planning policies are positive, the evidence from academic research is more tentative.

The rationale for mixed tenure[3] derives from the theory of “negative neighbourhood effects” - the notion that large concentrations of deprivation will have a negative effect on residents living in these areas, creating problems “greater than the sum of the parts”[4]. This has led to a belief that reducing concentrations of deprivation will directly benefit people on low incomes living in these areas.

This has driven thinking about new housing developments, estate regeneration and how to improve life on social housing estates.

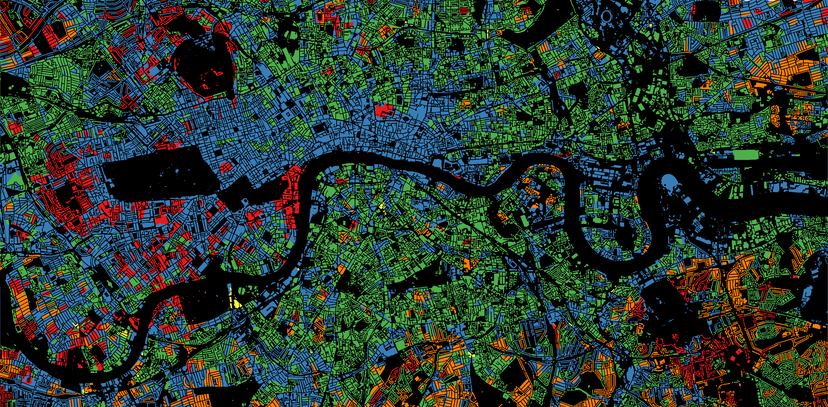

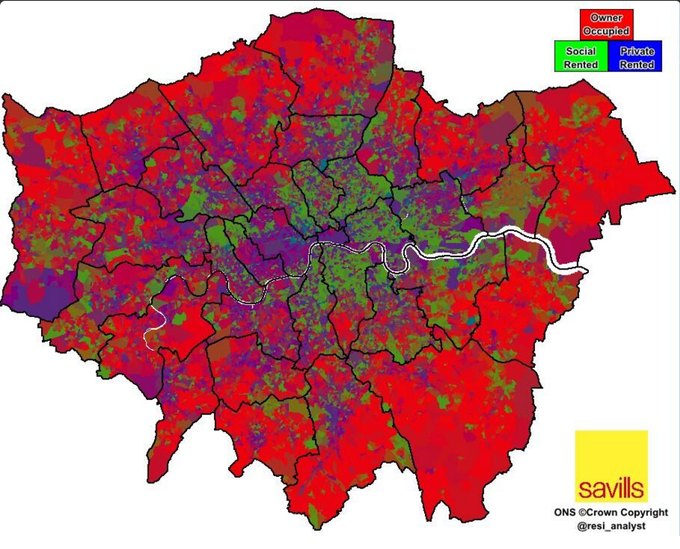

London Housing Mixing Map, by Neil Hudson 2014

Neighbourhoods that are mixed in terms of social structure, income and tenure are not a new thing. Nye Bevan’s words still resonate: “If we are to enable citizens to lead a full life, if they are each to be aware of the problems of their neighbours, then they should all be drawn from different sections of the community. We should try to introduce what was always the lovely feature of English and Welsh villages, where the doctor, the grocer, the butcher and the farm labourer all lived in the same street … the living tapestry of a mixed community."

But mixed housing programmes as we see them today, with strategic schemes to move affluent residents into low-income areas, are a relatively new phenomenon.

The rationale for mixed communities are that tenure mix will lead to interaction between tenure groups, provide supportive networks, and role model-relationships. However, the evidence shows is that interaction between tenure groups in mixed tenure neighbourhoods is not common and is often on a superficial level[5]. In some cases mixed housing even leads to stigmatisation of social renters by both owner-occupants and private renters, who perceive poorer households to be “inherently bad neighbours”[6]. Although there is evidence for a positive relationship between tenure mix and occupation, this relationship is more moderate than what ‘conventional policy wisdom’ claims[7].

Resent research also shows that the physical layout and design has a big importance for success[8]. Careful design, especially of shared spaces, can create spaces for people to meet and share experiences as well as a sense of ownership and something to be proud of. Tenure-blind integration, the so-called “pepper-potting”-structure where owner-occupied and rented homes are situated next to each other, prove to have the most positive effect in terms of cross-tenure interaction and creating and supporting a sense of community[9].

Conversely, more “segregated” or “segmented” mix, where tenure-groups are located in tenure-clusters show less or weaker benefits for marginalised residents[10]. This risks creating a divide between new and old residents and stigmatising social housing residents[11]. Tenures are often separated in the fear that if mixed, homes will be difficult to sell or rent on the market. However, the quality of design, layout and location have been found to be more important on house prices and there is little evidence that a spatially integrated mix of tenures has any impact on buying or selling homes[12]

BedZED Ecovillage with integrated mixed-tenure housing

There are strong arguments that mixed housing in itself is not enough to tackle some of the deep-seated social issues connected to areas with high deprivation[13]. If policies for mixed communities only focus on tenure distribution there is a risk of just moving social problems instead of solving them. We need to understand neighbourhoods as more than bricks and mortar. Estates and neighbourhoods are holistic systems with social networks, support systems, traditions, and shared histories.

When implementing mixed tenure programmes, one of the crucial factors for success is to simultaneously implement structural economic and social policies to support marginalised residents, through close collaboration with the local community and agencies[14]. If not, moving affluent residents into a deprived area risks displacing vulnerable residents and changing the social character of the neighbourhood[15].

It is also important that social infrastructure – critically providing spaces for residents to meet and get to know each other - is provided early in the life of a new development (too often this happens too late[16]). It is often within the first few months in a new home that new friendships and neighbourly supports are formed[17]. Understanding how to support and create social sustainable communities that work for residents from different backgrounds needs careful focus and better understanding if mixed housing is to succeed.

Finally, we need to bring our understanding of tenure, occupation and income mix in deprived areas up to date, to make sure that we understand the problems we are trying to fix. In many parts of London characterised by large proportions of social housing, right-to-buy policies mean that estates are much more mixed than in the past. Some right to buy leaseholders sublet their homes, so we see new groups of private renters; many of the original leaseholders have sold their homes to new more affluent owners, sometimes drawn to modernist designs and good internal space standards. The impact of high house prices and housing policy have meant that many social housing estates have become "mixed communities" by default, although in some, profound social problems still remain.

We need to update the evidence base on mixed communities asking how, and to what extent, recent policies and programmes have benefited residents of all tenures in helping access employment, tackle longstanding problems and improve quality of life. We need to understand what this means for more deprived residents in particular, as the number of supports and programmes shrink with budgets cuts. We need to learn from what is already known about how to make mixed housing developments work for everyone.

Footnotes:

[1] The full report can be downloaded here: hqnetwork.co.uk/document/5678

[2] Kearns et al (2013), Tunstall and Lupton (2010)

[3] Mixed communities policies can be divided into sub-categories of tenure mix, occupation mix, income mix and social mix. It has been found that neighbourhoods are generally more mixed in occupation and so when we speak about mixed communities in this context, it is mainly the processes seeking to create more balanced communities through tenure mix.

[4] Sautkina et al. (2012)

[5] van Ham (2010), Harrison (2015)

[6] Harrison (2015) p.5

[7] Sautkina et al. (2012), Livingston et al. (2013),

[8] Groves et al. (2003), Kearns et al. (2013), Bjoern (2015)

[9] Harrison (2015), Sautkina et al. (2012)

[10] ibid.

[11] Groves et al. (2003)

[12] Clarke (2012), Harrison (2015)

[14] Tunstall and Lupton (2010)

[15] Cheshire (2007), Harisson (2015), Bates et al

[16] Harrison (2015)

Bibliography:

- Harrison (2015), NHBC Report, Tenure integration in housing developments

- Sautkina et al. (2012), Mixed evidence on mixed tenure effects: Findings from a systematic review of UK studies, 1995-2009

- van Ham and Manley (2010), The effect of neighbourhood housing tenure mix on labour market outcomes: a longitudinal investigation of neighbourhoods effects

- Livingston et al. (2013), Delivering Mixed Communities: The Relationship between Housing Tenure Mix and Social Mix in England’s Neighbourhoods

- Tunstall and Lupton (2010), Mixed Communities Evidence Review

- Cheshire (2007), Are Mixed Communities the Answer to Segregation and Powerty

- Bates et al. (2013), Divided City – The Value of Mixed Communities in Expensive Neighbourhoods

- Bridge et al., 2012

- Groves et al. (2003), Neighbourhoods that work

- Kearns et al. (2013), How to mix? Spatial configurations, modes of production and resident perceptions of mixed tenure

- Bjoern (2015), Evidence for social effects of physical actions in marginalised residential areas

- Clarke (2012), The challenges of developing and managing mixed tenure housing

- Bailey and Manzi (2008), Developing and sustaining mixed tenure housing developments

- Bernstock (2008), Neighbourhood Watch: Building New Communities: Learning Lessons From the Thames Gateway

- Rowlands et. al. (2006), More than tenure mix: Developer and purchaser attitudes to new housing estates

- Woodcraft and Bacon (2011), Design for social sustainability