Imogen has been a intern at Social Life since January 2019. Originally from New Zealand, she is a recent graduate from the University of Auckland where she completed her dissertation on the impact of gentrification on the suburb of Glen Innes with a particular focus on examining how the dialect of urban planning has been utilized as a justification for gentrification and 'regeneration.'

In this blog, I share the story of my home town - Tāmaki Makaurau (Auckland) in Aotearoa (New Zealand). I recently completed my undergraduate degree in urban planning during which I wrote my dissertation research on what has been argued is a case study of gradual state-led gentrification in the suburbs of Glen Innes in Aotearoa’s largest city - Tāmaki Makaurau. I explored how urban planning – as a discipline – is one of immense power and influence, having both the capacity to encourage human freedom and limit it.

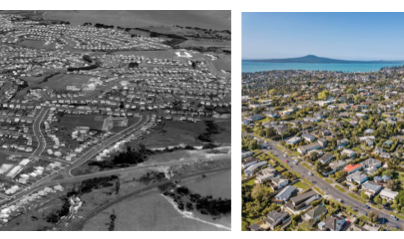

Glen Innes was established in the late 1960s as an area of high state housing stock (state housing is similar to social housing in the UK). It was primarily developed to house people being displaced by the processes of inner city gentrification in Tāmaki Makaurau.

Historically, Glen Innes has for the most part been a low-income working class suburb, home to diverse cultures with high levels of Pacific, Māori and Asian representation as well as Iraqi, Iranian and Fijian Indian residents. Over time the Pacific and Māori communities have grown in number laying the foundations for a tight-knit, proud and flourishing local community. Many families moved together to Glen Innes (after being displaced from Aucklands inner city suburbs), bringing their strong and intergenerational community ties to their new home .

Glen Innes’ location – close to the waterfront, nature, beaches (and potentially the last piece of ‘undeveloped’ coastline in Tāmaki Makaurau) and being just 10km from the city center – has long had the area pegged as an area of significant ‘development potential.’ In the latter half of the 20th century, a series of smaller projects focused on increasing amenities, services and cultivating a better built environment in Glen Innes spurred interest in the ‘development potential’ of the area. A change in housing policy after 2010 was followed by a larger, more comprehensive state-led regeneration project that put the urban planning policies of ‘mixed communities’, ‘pepper-potting’ (the ‘sprinkling’ of state housing amongst wider private housing) and privatization at its foundation.

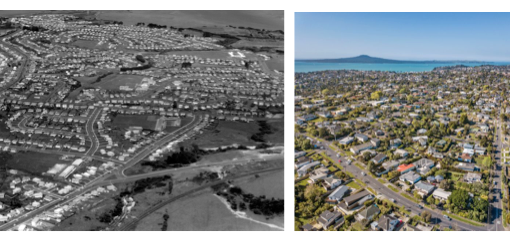

Over time, intense community resistance to the project and a series of protester/police clashes have seen the regeneration project in Glen Innes turn into a national controversy. Re-housing policies saw long-term residents who had been promised ‘homes for life’ being removed from the area completely and pushed further out from the city center. Over time, the policy of ‘mixed communities’ has been utilized as a justification for re-development and has ultimately resulted in the gentrification of Glen Innes and its surroundings by predominantly Pākehā (white) middle-upper class residents.

Many feel that this has erased an entire pre-existing community. The ‘rebranding’ of the area – which sought to attract middle and upper class residents and distance Glen Innes from past (as a predominately working class area) – was resulting in a gradual class and demographic shift. As a result, Glen Innes now mirrors its surrounding affluent neighbourhoods, with rising house and rent prices, which are having the effect of outpricing those who have lived in Glen Innes for generations.

It is now 2019 and the Glen Innes that once was no longer exists. Where there was once a flourishing, thriving community with strong networks and ties I found there is now a fragmented, disjointed one. Street and suburb names have been changed to attract a new demographic, all pre-existing state housing has been demolished, entire city blocks have been reformulated, and residents have been displaced.

The erasure of an entire community and its history within the urban planning landscape of Tāmaki Makaurau, is a devastating foreword on the future of social housing policy in Aotearoa. It is a worrying example of how the policies of urban regeneration and the language of development discourse can displace communities and their well-established support strucures; polarising cities along the lines of race and class.

If you are interested in learning more about Glen Innes the following links are good places to start:

https://news.aut.ac.nz/informer/the-re-branding-of-glen-innes-redevelopment-or-disestablishment